Setting the clock: Okinawan time or military time?

They say that time flows slower in Okinawa, but for me at least it seems to be flying. Half of my time in the field has already passed. After my quarantine in Tokyo, I arrived on the island in mid-January and first settled in a dormitory at the University of the Ryukyus, where I stayed for about a month. With a state of emergency still in place it was hard to meet people, so I spent most of my time in the university library, browsing through dugong catch quotas of the early 20th century and descriptions of environmental problems Okinawa and therefore the remaining dugongs are facing. Red soil runoff is killing reefs. Fertilizers are used excessively and are eventually washed into the ocean. Infrastructural and tourism development projects are burying coastal waters. And of course the never-ending story of militarism on the island.

The University of the Ryukyus is situated in the densely populated southern part of the island, just a thirty minute walk from the notorious Marine Corps Air Station Futenma. Here the sound of Helicopters and V-22 Osprey aircrafts as well as fighter jets taking off from Kadena Air Base, a 20 minute car ride away, is ever-present. After familiarizing myself with Okinawa’s militarized environment, I felt it was about time to visit what was about to become my main field site: the construction site of a new military base in Henoko and its surrounding area. Driving up north the scenery changed from impermeable concrete to lush green. I also saw fewer helicopters in the sky. Some, but not as many. There is no place on Okinawa where you would be surprised to see military vehicles on the street carrying explosives and soldiers or an Apache flying way too low over your head.

My destination, the northern part of Okinawa Main Island, is less populated than the south. Especially the east coast, where Henoko and the construction site are located, impresses with dense forest, clear waters, lively reefs and intact sea grass beds. These sea grass beds are the feeding grounds of the dugongs. Villages here are confronted with the problem of depopulation as young people are moving to the cities. Some of them are house owners, but they are hesitating to rent out their empty property because of obligations towards their ancestors: central to most houses is the family altar, which many people do not want to entrust to strangers. A lot of them plan to use their houses in the future again. Some hope for new economic opportunities, once the base is built. And of course in recent years subsidies have been flowing from Tokyo down to these little villages. Compensation for the nuisance to come, one could say.

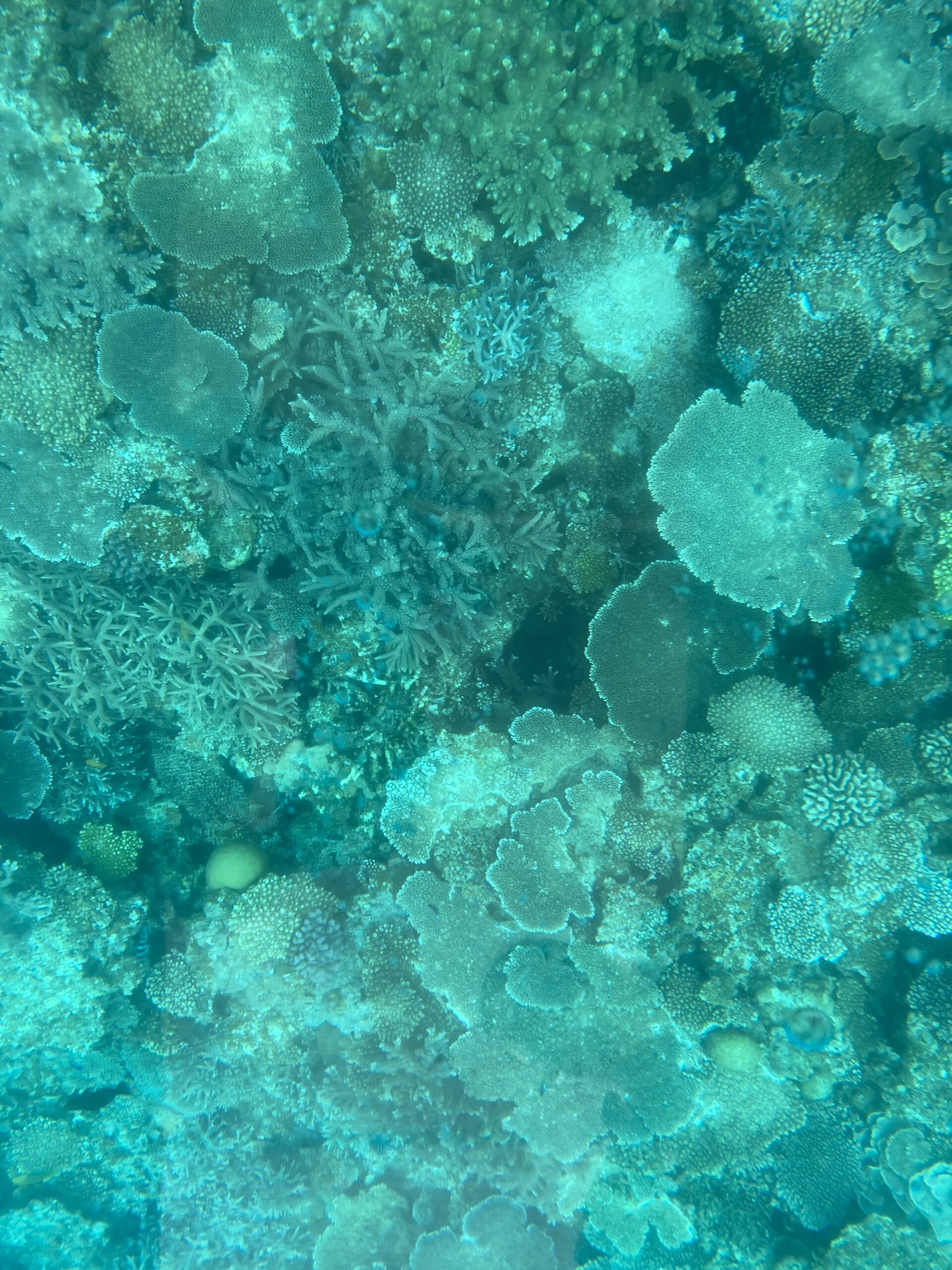

During my short trip to the north, I visited Oura village, north of Henoko, and nearby Oura Bay, a place busting with biodiversity. Scientists suggest that this bay is home to 5.300 species, including rare blue corals, recently discovered crab species, and of course the Okinawa dugong. Not just truckloads but literally shiploads of soil are dumped Into this ecosystem every day, all for the construction of the new military base. Actually seeing the massive scale of the project was impressive and scary at the same time. Impressive from a viewpoint of logistics and construction, scary from a viewpoint of environmental destruction and future problems including noise pollution and possible accidents for adjoining small villages like Henoko and Oura.

During my short trip to the north, I visited Oura village, north of Henoko, and nearby Oura Bay, a place busting with biodiversity. Scientists suggest that this bay is home to 5.300 species, including rare blue corals, recently discovered crab species, and of course the Okinawa dugong. Not just truckloads but literally shiploads of soil are dumped Into this ecosystem every day, all for the construction of the new military base. Actually seeing the massive scale of the project was impressive and scary at the same time. Impressive from a viewpoint of logistics and construction, scary from a viewpoint of environmental destruction and future problems including noise pollution and possible accidents for adjoining small villages like Henoko and Oura.

How was the construction affecting these villages? What effects could already be seen in the environment? How would people relate to a project that was decided upon over their heads, despite a 2019 non-binding prefectural referendum in which 72% of voters said no to the base? And what about the dugongs that were reported to frequently visit Oura Bay until construction work commenced? I decided it was time for me to live here.

Making a home in the field, navigating social sensitivity, and experiencing opposition

With a little help, I managed to settle into an empty house in Oura village. The owner was one of the few people in the village who were willing to rent out their empty property. It was about time for a human being to move in again, he thought. With the forest around the corner, it is just a matter of time until other tenants move into these empty structures: insects. Fighting off giant spiders, poisonous centipedes and ant colonies, I made the house into a home. I do not regret the decision moving up here. Living here has made me realise what a sensitive topic the base issue actually is. Opinions differ, so in some situations it is wise not to touch upon the issue. At the same time, some people feel disempowered by the fact that the government, despite local opposition, pushes the project through. Others have a make-the-best-out-of-it attitude and take up jobs related to the construction work.

Living close by, I was able to visit protest sites on land and water. Here the oppositional spirit stays strong. People are gathering in front of the main gate of Camp Schwab at Henoko, holding sit-ins day after day after day, not willing to accept the new base. This has been going on for years. So has the sea-based protest during which protesters penetrate the construction site in kayaks to slow down construction work. Slowing down landfilling aims at a possible change in government or international relations that might make the base itself obsolete. The daily actions are also a symbolic reminder to the current government and the U.S. military that some of the opposition cannot be silenced with subsidies.

Changing currents and the dignity of the dead

I also had the opportunity to join reef checks conducted by environmental organizations and learn a lot about the effects of the construction work not just on dugongs, but on corals, shellfish and sea turtles. Environmentalists fear that the construction will change the flow of currents within Oura Bay, which may affect reef structures that are located at a considerable distance.

In addition to environmental and human rights issues, recently a new matter made it on the protest agenda. The government plans to use soil from the southern part of Okinawa Main Island for the base landfill. In this area, many people perished during the battle of Okinawa, also known as the Typhoon of Steel. These include American and Japanese soldiers—including recruits from the Korean Peninsula and Taiwan—as well as civilians. According to protesters, the soil from this area is filled with human remains. In the eyes of the opposition, to use this very soil to build yet another military facility is a disgrace.

Meanwhile COVID is hovering over my fieldwork like a cloud always ready to burst. After the state of emergency was lifted in March, it became easier to meet in person for interviews and to join protesters on their daily sit-ins. However, since the Corona cases were rising again, not just in Japan’s major cities, but also in Okinawa, the prefectural government decided to declare a proactive manen bōshi (“prevention of spreading”) strategy, which is basically one step before a state of emergency. Again, restaurants close early and no official protest gatherings are organised in Henoko, although some protesters gather on an individual basis.

Non-human depopulation?

And the dugongs? No dugongs have been sighted in the area since construction work started. It seems as if the sound-sensitive dugongs decided to leave this noisy place. Not only Oura Bay proper, but also the coast of Kayo, a village situated just a couple of kilometres up north and a place where until recently dugong trenches were frequently spotted, seems to have lost its most gentle inhabitant. This is another type of depopulation, which may have been caused by the increased frequency of helicopters flying along the coast from a northern jungle warfare training centre in Takae to bases in the south or by the increased traffic on the sea, with ships bringing soil to the construction site.

Does that mean that these places are not relevant for dugongs anymore? For the time being, it is not very likely that dugongs are still present in this area, but as one interlocutor of mine put it: it is also about saving feeding grounds for dugongs to return in the future. After all, feeding trenches were found last year in areas where the dugong was supposed to be extinct since the 1960s, such as Iriomote Island and Hateruma Island, 500 kilometres south of Okinawa Main Island. Other trenches were found in the waters of Nakijin village on the western side of Okinawa Main Island. In the past, dugongs were oscillating between Nakijin and Oura Bay. Although big parts of Henoko’s sea grass beds have already been destroyed, there is still a chance of dugongs returning to the area, if the opposition achieves a construction stop.

The political meaning of this animal, the complex social networks that motivate or prevent people from joining the protest, and the fact that international relations manifest themselves here in solid matter and destructive force, makes the Oura Bay area a fascinating field site. I am happy to be here, despite all COVID-related hurdles. With the heart-warming help of interview partners and neighbours, it feels like I am making progress here in the field. Occasionally I find the time to enjoy the beauty of Okinawa without thinking about helicopters, protests and dump trucks. In these moments, I just wished time was flowing a bit more slowly…