“We can safely say that we have helped put multilingualism on the agenda,” says Professor Unn Røyneland, Center Director of MultiLing.

1,570 conference presentations and guest lectures in more than 40 countries. 640 research papers, 40 books and special issues. 20 doctoral theses, and six more under way.

These are just some of the results after a decade of research at MultiLing - Center for Multilingualism.

“Multilingualism researchers around the world know who we are. We have become internationally known and have put Norway on the map as one of the strongest research environments in our field. We are very proud of that,” says Røyneland.

The work will continue

In May 2024, MultiLing’s status as a Norwegian Centre of Excellence (CoE) comes to an end, and the Center will no longer be funded by the Research Council of Norway. However, the research on multilingualism continues.

“This field of study has been established as a new area of research at the Department of Linguistics and Scandinavian Studies, with a staff of eight who will continue the scientific effort in the years to come,” says Røyneland.

This will be done through various research projects and with the solid expertise that the research environment has built up in MultiLing’s time as a Centre of Excellence.

The Center’s Socio-cognitive Lab will also play a central role in the multilingualism research going forward. It uses innovative methods such as EEG, which records the brain’s electrical activity, as well as eye tracking and other multilingual assessment tools.

“We have also established a brand new international Master's Programme in Multilingualism designed to ensure recruitment to the field,” Røyneland says.

Focused on its social mission

MultiLing’s research has focused on three areas: Multilingual competence and development across the lifespan, multilingual practices in families, at school and in the workplace, and language ideologies and policies in the multilingual society.

The vision has been clear: to gain knowledge about the challenges and opportunities multilingualism presents, both for the individual and for society.

“We have contributed to making society better equipped to manage linguistic diversity,” says Professor Emerita of Linguistics and former Director of MultiLing, Elizabeth Lanza.

The goal has been to contribute to basic research in the field, and everything the Center has done has been impacted by this societal mission.

“We have targeted research that benefits society. The goal has been, and will continue to be, to contribute to more research-based knowledge that in turn will improve the lives of multilinguals,” Lanza sums up.

Why are some languages regarded as inferior?

After studying multilingualism in the very young, the old, and those in between, MultiLing’s research has helped improve our understanding of what multilingualism means for the individual and for society.

For example, it has identified trends in language development, shattered myths about multilingualism, and looked at how different languages are valued differently by society.

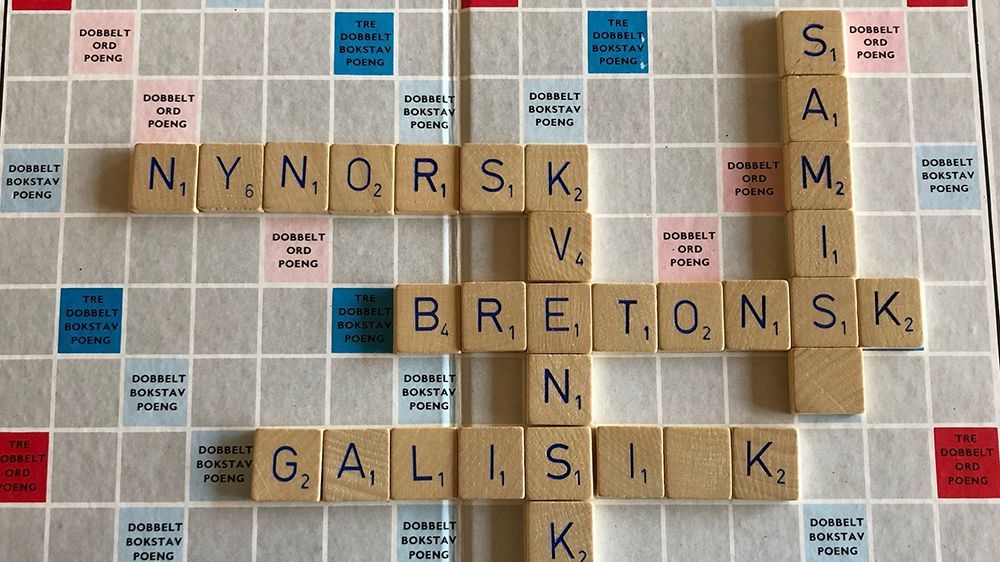

“We have shown that negative attitudes to minority languages still exist in Norway, despite a new language policy that recognizes linguistic diversity,” says Røyneland, adding:

“In Norway, as in the rest of the world, some languages are regarded as less important or less valuable. This, of course, is related to the status of those who speak the languages concerned.”

She points out that there is a tendency for certain forms of multilingualism to be regarded as a resource, while other forms are portrayed as problematic.

According to Røyneland, this can have major consequences for the users of various languages, and can ultimately lead to language death, or that people cease using a language – as has been the case with the Kven language and several of the Sámi languages.

“Our researchers try to promote the value of all languages,” adds Røyneland.

Is “chat speak” taking over?

MultiLing has also researched the spoken and written language that young people use. This has included exploring the idea that young people are becoming steadily poorer at writing standard Bokmål or Nynorsk, the two official written norms of Norwegian.

Is it the case that the creative language used in private digital communication – so-called chat speak, which is characterized by abbreviations, dialect forms, the use of English and very little punctuation, is affecting their ability to write formally?

“No, not necessarily,” answers Røyneland and points to their research. This shows that most young people know how to switch between different norms and have no difficulty in doing so. When they write something formal, they stick to standard written language. When they chat on social media, a different norm applies where using correct punctuation would be strange.

“We think it is positive that they can vary their written language relative to context. It means that they have a large linguistic repertoire,” she explains.

The research has also challenged existing myths, amongst others the myth that you should not speak several languages to children. It is a widespread belief that multilingualism can confuse the youngest children and that it can have a negative impact if their parents speak to them in different languages.

“Our research has shown this not to be true; there are no cognitive disadvantages in doing so. Quite the opposite – multilingualism can have a positive impact. And we have visited day care facilities, child health centres and schools to inform and educate about this,” Røyneland says.

---690x514.jpg)

Has brought multiple fields together

“MultiLing’s work has created ripple effects in other ways as well. For example, it has contributed towards bringing together researchers from the humanities, social sciences, psychology and natural sciences to undertake research on multilingualism,” Lanza explains.

“Previously, researchers from different fields have been interested in and worked on many of the same topics, without collaborating much. We have managed to promote a new standard where the cognitive, linguistic and social aspects of multilingualism are investigated in relation to one another.”

She is convinced that this has improved their work and made it more relevant, and points to the research on dementia and aphasia as an example of this.

“When people who are multilingual get dementia or aphasia, they can experience language problems. The difficulties they experience are not necessarily the same in the different languages that they know. Therefore, it is vital for people with dementia or aphasia not just to be tested in Norwegian, as is often the case in Norway, but also to be tested in their first language(s).”

Through several research projects, researchers at MultiLing have developed new tools and methods that ensure that multilinguals with dementia and aphasia are diagnosed more precisely, which leads to a more accurate treatment.

The way forward

While Røyneland, Lanza and the other researchers at MultiLing can point to many achievements, such as publications, conference presentations, international recognition, contributing to the new Norwegian Language Act, new curricula and a report for the Norwegian Truth and Reconciliation Commission, there is still much unchartered territory in the field of multilingualism.

Moreover, the new knowledge they produce needs to be communicated to society, to families, to day care facilities, schools and other institutions, in order for the knowledge to have a cultural and political impact.

“To facilitate better communication and prevent social exclusion, we need a nuanced understanding of multilingualism and the experiences of minorities. We still have some way to go before this knowledge is put into practice in institutions and in society,” concludes Centre Director Røyneland.

About MultiLing

MultiLing - Center for Multilingualism, is a research center funded by the Norwegian Research Council as a Center of Excellence at the Department of Linguistics and Scandinavian Studies at the University of Oslo.

The center is organized around three mutually dependent themes, which form the backbone of the center's research activities:

- Multilingual competence over the lifespan. How multilingual children, youth, and adults acquire the languages they know, with a focus on how multilingual competence changes throughout life.

- Multilingual practice and language choice over the lifespan. How multilingual children, youth, and adults use the languages they know, with a focus on how multilingual usage changes throughout life.

- Multilingualism, ideologies, and language policies. How social and political power relations affect multilingual acquisition and use, both at the individual and group level.

MultiLing brings together research areas that have traditionally been separated within linguistics, specifically sociolinguistic and psycholinguistic approaches to language and multilingualism.

The center also combines various research fields such as linguistics, sociology, psychology, education, anthropology, and neuroscience.

Relevant study programs and courses

- Multilingualism (master's two years)

- MULTI2110 – Introduction to Statistical Analysis for Language Students

- MULTI2150 – Project-based Research in Multilingualism

- MULTI4100 – Theoretical Foundations of Multilingualism

- MULTI4110 – Introduction to Statistical Analysis for Language Students

- MULTI4120 – Cognitive Aspects of Multilingualism

- MULTI4130 – Social Aspects of Multilingualism

- MULTI4150 – Project-based Research in Multilingualism

- MULTI4160 – Multilingualism Specialisation A

- MULTI4180 – Supervised Reading in Multilingualism

- MULTI4190 – Master's Thesis in Multilingualism

- MULTI4195 – Master's Thesis in Multilingualism